When Traditional Recipes Became Acts of Resistance and Cultural Preservation

The year was 1945, and as Sukarno declared Indonesia’s independence from Japanese occupation, something profound was happening in kitchens across the archipelago. Indonesian cooks weren’t just preparing meals, they were reclaiming their culinary identity after years of colonial influence that had attempted to reshape not just their politics, but their palates.

This phenomenon wasn’t unique to Indonesia. Across the globe, independence movements have consistently recognized that food is far more than sustenance, it’s cultural DNA, and protecting traditional recipes becomes an act of resistance, preservation, and ultimately, liberation.

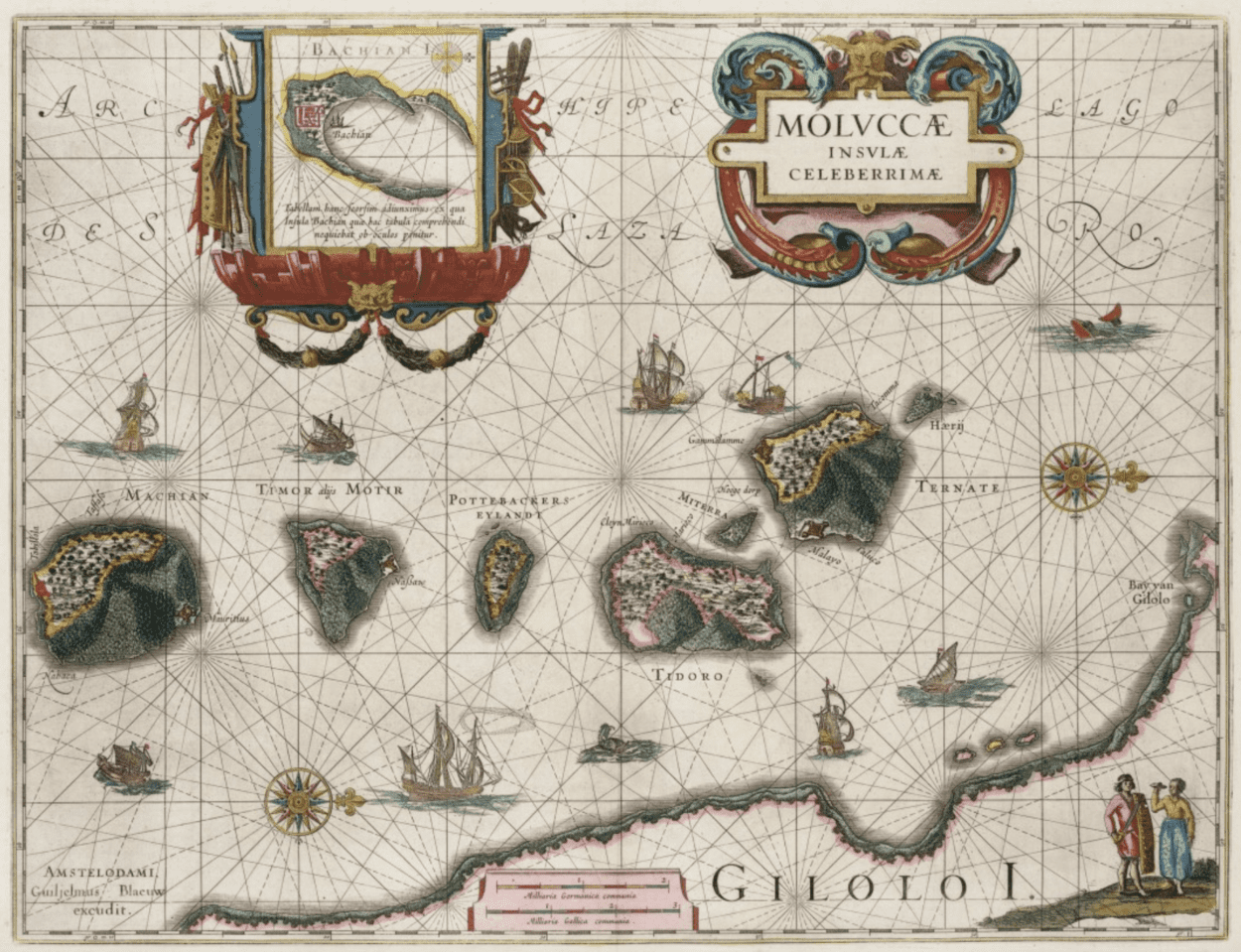

Doc: Princeton.edu. 1640: Blaeu, Willem Janszoon, 1571–1638. “Moluccæ insulæ celeberrimæ.” Copperplate mapFirst large-scale map of the Moluccas, oriented with north to the right. The equator touches Tidore. The inset map of Bachian Island

Doc: Princeton.edu. 1640: Blaeu, Willem Janszoon, 1571–1638. “Moluccæ insulæ celeberrimæ.” Copperplate mapFirst large-scale map of the Moluccas, oriented with north to the right. The equator touches Tidore. The inset map of Bachian Island

The Spice Trade: Seeds of Culinary Power

Long before political independence, the Indonesian archipelago was the epicenter of the global spice trade. The Banda Islands produced nutmeg and mace, the Moluccas yielded cloves, while Java and Sumatra offered black pepper, cinnamon, and cardamom. These weren’t just commodities, they were the foundation of culinary traditions that would define Indonesian cuisine.

European colonial powers fought wars over these spices, understanding their economic value but missing their deeper cultural significance. For Indonesians, spices like galangal, turmeric, coriander, and lemongrass weren’t just flavor enhancers, they were medicine, ritual elements, and identity markers. The complex spice blends called “bumbu” became the soul of Indonesian cooking, each combination telling stories of regional traditions and family heritage.

Photo Doc: The Apurva Kempinski, Majapahit Dining

Photo Doc: The Apurva Kempinski, Majapahit Dining

When Dutch colonizers attempted to monopolize spice production and trade, they inadvertently strengthened Indonesian culinary identity. Home cooks became guardians of spice knowledge, preserving not just recipes but the wisdom of spice combinations passed down through generations.

Rasa Nusa. Photo doc: The Meru Sanur

Rasa Nusa. Photo doc: The Meru Sanur

The Kitchen as Battlefield

Colonial powers understood the significance of food in cultural identity, which is why culinary suppression often accompanied political dominance. The Dutch in Indonesia promoted European ingredients and cooking methods in urban areas, while the British in India attempted to “civilize” local cuisines by introducing bland, European style preparations in colonial clubs and administrative centers.

Yet in home kitchens, markets, and village celebrations, traditional recipes survived like underground resistance movements. Indonesian mothers continued grinding spice pastes by hand for rendang, even as imported European spices appeared in colonial markets. Indian families maintained their complex curry traditions despite British attempts to simplify “curry powder” into a single commercial blend.

Photo Doc: Dedy H.Siswandi

Photo Doc: Dedy H.Siswandi

Indonesia’s Culinary Independence Movement

Indonesia’s struggle for culinary independence began long before political independence. During the Dutch colonial period, Indonesian cuisine adapted and evolved, incorporating some European ingredients while fiercely protecting its essential character. The Dutch introduced potatoes, tomatoes, and various European vegetables, but these were absorbed into Indonesian cooking techniques rather than replacing them.

The real preservation happened at the grassroots level. Street vendors continued serving traditional favorites like gado-gado and satay. Beyond its cuisine, Indonesia’s beverage heritage also thrives, most notably jamu, a traditional herbal elixir long valued for its medicinal properties. In many places, jamu is still sold in the time-honored way: carried in glass bottles within a woven basket, slung over the shoulder or balanced on the back, as vendors roam the streets.

Home cooks maintained the laborious process of making proper sambal, grinding chilies with traditional stone mortars. Regional specialties like Padang cuisine from West Sumatra remained largely untouched by colonial influence.

Dengke Mas Na Niura

Dengke Mas Na Niura

Consider naniura, the traditional Batak dish from North Sumatra often called “Batak sashimi.” This preparation of raw ikan mas (goldfish) marinated in asam jungga (torch ginger flower) with a complex blend of herbs including andaliman (Batak pepper), turmeric leaves, and torch ginger showcases the sophistication of pre-colonial Indonesian cuisine. Unlike the more famous rendang or nasi goreng, naniura represents the deep regional diversity that colonial powers never fully understood or controlled.

Photos doc. William Wongso

Photos doc. William Wongso

Food as Political Diplomacy

Today, Indonesian cuisine serves as powerful cultural diplomacy. During the G20 Summit in Indonesia, traditional Indonesian dishes became diplomatic tools, with the country serving selada udang Bangka (Bangka prawn salad) and terik tempe bacem (glazed fermented soybean) to world leaders. These culinary choices communicated cultural richness and national pride more effectively than formal speeches.

Lawa Bale/ Photo doc. The Westin Resort Bali Nusa Dua

Lawa Bale/ Photo doc. The Westin Resort Bali Nusa Dua

This culinary diplomacy extends beyond state functions. Indonesian restaurants worldwide serve as unofficial embassies, introducing international audiences to Indonesian culture through food. Chef William Wongso, often called the “culinary ambassador of Indonesia,” has spent decades documenting and promoting Indonesian cuisine internationally, understanding that food can build bridges between cultures.

Photo doc. Gowtham/Pexels

Photo doc. Gowtham/Pexels

Parallel Struggles: India’s Spice Revolution

India’s culinary independence movement followed a similar pattern. British colonial authorities often dismissed Indian cuisine as “too spicy” or “unhygienic,” promoting bland European-style cooking in colonial institutions. Yet independence leaders like Mahatma Gandhi recognized food’s cultural importance, making salt, a basic cooking ingredient, the symbol of his famous march against colonial oppression.

Post-independence India saw a renaissance of regional cuisines that had been marginalized during colonial rule. Bengali cuisine, Gujarati vegetarian traditions, and the diverse regional curries of South India all experienced revival as expressions of cultural pride.

Vietnam’s Pho: A Bowl of Resistance

Vietnam’s signature dish, pho, tells a similar story of culinary resilience. During French colonial rule, Vietnamese cooks adapted French beef-eating habits but created something entirely new. Pho emerged as a fusion that maintained Vietnamese flavor principles, the clear, aromatic broth, the fresh herbs including cilantro, Thai basil, and sawtooth coriander, the complex layering of star anise, cinnamon, and cloves, while incorporating beef in a uniquely Vietnamese way.

Iga Konro Bakar. Photo doc: The Westin Bali Nusa Dua

Iga Konro Bakar. Photo doc: The Westin Bali Nusa Dua

The Sacred Nature of Authenticity

Here lies a crucial understanding about heritage cuisines worldwide: it is hard and sacred to put the word “authentic” in many countries’ heritage culinary traditions, including Indonesia. Taste and preference are based on individual background and family traditions, when and where people grow up shapes their understanding of “correct” flavors. A rendang from one family in West Sumatra may differ significantly from another’s, yet both are equally “authentic” because they represent genuine family traditions passed down through generations.

This regional and familial diversity makes heritage cuisines both challenging and beautiful. Unlike cuisines with more standardized preparations, traditional dishes carry the DNA of family history, making each version a unique cultural document.

Photo doc: The Apurva Kempinski Bali

Photo doc: The Apurva Kempinski Bali

The Call to Preserve

The responsibility of preservation extends beyond professional chefs to every person connected to culinary traditions worldwide. Whether it’s learning to properly balance spices in Indian curry, mastering the art of pho broth in Vietnam, or understanding the essential tastes in Indonesian cuisine, spicy, sweet, savoury, and sour, each act of culinary learning becomes cultural preservation.

When families across the globe teach children to recognize the aroma of properly toasted spices, the technique of hand-grinding sambal in Indonesia, or the delicate timing of pasta in Italy, they’re ensuring these traditions survive. Heritage food from every nation deserves our pride and protection. These recipes carry the wisdom of ancestors, the stories of survival, and the essence of cultural identity. Preserving them isn’t about museum piece recreation, it’s about keeping living traditions alive for future generations who deserve to taste their heritage.

Editor: Gaby Nareswari